What does Zehra Doğan want?

"What we see in this exhibition are works created by Zehra Doğan with persistence and resilience during her prison sentence, using any surfaces, objects and materials she could find (including brushes made out of her own hair and menstruation blood used as paint; an expression of body politics in its fullest sense) and other manifestations of the alternative realm she created while in prison."

29 Ekim 2020 04:02

Zehra Doğan’s first solo show in Turkey, Unseen, curated by Wenda Koyuncu and Seval Dakman, opened as part of the Debating Nationalism program currently in progress at Kıraathane.

The exhibition is comprised of works created by the artist during her imprisonment: the diaries she kept, some voice recordings and other such records of prison life. Zehra Doğan’s personal story, the life she lived (or indeed the life she could not live) provides not only the material for her works but also a means of interpreting those works. Here is a quote from the exhibition text:

“[Zehra Doğan is a] Kurdish journalist and artist. She was put on trial for sharing on social media paintings she had made during the curfew and security operations in the Nusaybin district of Mardin and writing a news story based on the notes of a 10 year-old child… she was convicted of “terrorist propaganda” and sentenced to 33 months of imprisonment.”

What we see in this exhibition are works created by Zehra Doğan with persistence and resilience during her prison sentence, using any surfaces, objects and materials she could find (including brushes made out of her own hair and menstruation blood used as paint; an expression of body politics in its fullest sense) and other manifestations of the alternative realm she created while in prison. The exhibition presents a book of dreams and fairy tales created in a space of confinement by someone who is literally reduced to ‘bare life’ (as coined by Agamben) and still manages to transform the absolute scarcity with which they are confronted into infinite possibility. The title of the exhibition is significant in that sense. All the things which had been sent inside after being ‘seen’ by the prison authorities are thus made instrumental in her act of showing to the world all that remains ‘unseen’, hidden out of sight because they are found objectionable. A remarkable counter manifesto written from the inside to the outside, upon the materials of the outside. [1]

After she was released, Zehra Doğan held her first exhibition at the Tate Modern. In this exhibition, titled E Li Duman (What Remains), the artist used found objects from devastated sites such as Cizre and Nusaybin. In that exhibition she showed traces of a destruction which cannot be shown here (for obvious political reasons). At the time, I explored the reasons why Doğan was unable to exhibit these pieces attesting to violence (burnt carpets, parts of shoes, and other ‘damaged’ objects, etc.) in Istanbul in an article I co-wrote with Wenda Koyuncu, curator of the show at Kıraathane. [2] That exhibition became politically significant here for the very reason that it could not be staged here. Such works/exhibitions can also be recorded in history by their non-presence. Our article suggested that Zehra Doğan’s exhibition was a lot more than an exhibition, it was a social act, a situationist act even. It was Doğan collecting the evidence of violence and inviting the visitors to a confrontation, to a leap into action, here and now.

This current exhibition engages in a similar move: It invites the onlookers to a place that is violence-ridden and yet does not allow its counter-stand to lapse into the rhetoric of victimhood. All of the objects, texts and images that can be seen in the exhibition space are engaged in an act of breaking through walls – the walls put up by official authorities, the devices of confinement. Walking around the exhibition is a way of tapping into the mind of someone who is ‘inside’. Naturally, there is gloom and violence in the air, but one can also feel the defiant spirit that transforms the exhibition into action, maybe aligning with a politics of emotions. As an imprisoned woman, the artist’s use of objects and states of femininity as a political device – or a surface – introduces a feminist streak into the exhibition. Because ultimately, the governing authority responsible for imprisonment is usually male, either in the real or metaphoric sense, and those inside are viewed through the male lens. The works in this exhibition function to turn that gaze in the direction of things that have been dismissed, ignored, or left unseen. It is the embodiment of what bell hooks calls “the oppositional gaze”.

Another function the exhibition fulfils most successfully is the development of a counter-rhetoric by embracing everything, every little piece, every image that has ever been considered abject, reminding us of works by transgressive artists such as Tracy Emin. It goes without saying that one of the operational strategies of governing bodies is to create a catalogue of abject elements – material and conceptual – and develop them into images that are anathematic and perilous. Embracing the abject, turning it into a means of expression, making it representable is therefore a political move.

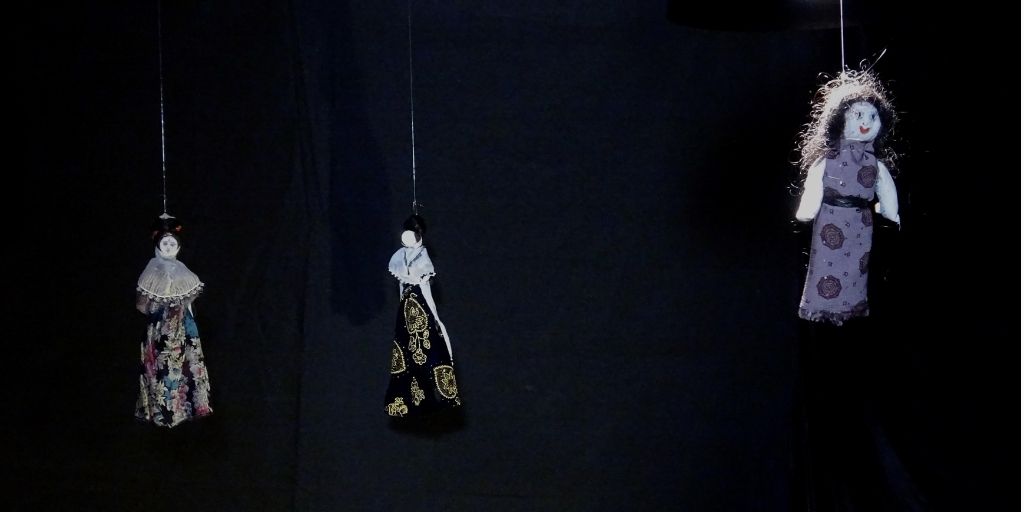

Jinén Li Hember / Karşıdaki Kadınlar (Women Across), Zehra Doğan.

"My mother and older sister always found new ways of giving me the means of making art in prison. I think one of the most effective methods was my mother bringing me her own dresses as part of the clean laundry package. I would paint on these dresses and give them to the guard to be returned to my mother as “dirty laundry” at the next visit. My mother would collect these and bring me different dresses for me to paint on.

While reflecting on representation and disregard, one of the most appropriate utterances I have recently come across on this matter belongs to Butler: “an insurrection at the level of ontology”. In her book on mourning and violence [3] Butler comments that those who are not allowed to give expression to their existence and are rendered nulus nomen, and thus engage at one point in an ontological rebellion, theirs is an insurrection of existence. The disregarded can include everyone who chooses to remain or is forcibly cast outside the representational schemata of official ideology: immigrants, gays, minorities, rogues, radical political thinkers, prisoners of conscience or the poor. When they attempt to make their existence heard and seen, they rip through the curtain of invisibility and have their existence registered, whether in writing, action, performance, imagery or any other act that supposedly disturbs the peace. This can be our departure point in our exploration of what Zehra Doğan wants as an artist: above all else, she wants her existence to be registered and for it to resonate within the order of things. It is a political, esthetical, symbolical, or physical resonance.

The question of what Zehra Doğan wants, which is also the title of this piece, was also asked years ago in the title of an interview held with Şener Özmen: What Does Şener Özmen Want? [4] The scope of the question was expanded in that interview: this individual before us, as an artistic and political entity in the world, what do they want? What is the meaning of all their works and interventions? What is the intention behind them? Gradually, the interview focuses on Özmen’s video titled “What Actually Does an Artist Want?”. In this video, the artist is alone on some barren land, talking in an exalted manner. But his voice is not heard because military planes are flying over his head and the anonymous sound of the martial machine drowns out the private sound of the talking subject. The critical point is that the machine annihilates the voice both literally and metaphorically. So, the artist never gets to explain what it is that he wants. This is not a cultural or relational crisis, it is an ontological crisis. In other words, the artist does not exist, his voice is eliminated. Nevertheless, in that video the inability to narrate becomes the narrative itself. Through an ironically charged political move, the unsaid is given a voice.

Ez u Ca xwe / Ben ve annem / Me and my mother, Zehra Doğan

"While I was in prison, my mother made two dolls out of two old branches she found in the garden. She cut up her own clothes to make dresses for these dolls. One doll was meant to be me, and the other doll was my mother. She had some hair of mine at home, the hair that I had shed and collected, and she had kept at home, she stitched it on my doll’s head. My little niece Havin also made a doll and did the same. So, they made for themselves these Zehra toys, and in their own way, they liberated the prisoner Zehra. They did not accept that I was inside. They put me in a corner of the room, as if I were at home, none of this had happened, as if I were free and by their side…”

Zehra Doğan also makes a move to be heard in this ontological sense but she does not do it with irony. She is in-your-face and serious in her intention to raise her hushed voice to full volume. To that end, she utilizes her own existence, her body, and all the unconventional materials – which she adopts like a practitioner of arte povera – as a megaphone. This metaphorical megaphone produces harsh and heavy sounds. In order to hear me, you too must feel this harshness and heaviness.

One work in the exhibition achieves this exquisitely: On a payphone installed in the exhibition, you can listen to the phone conversations Doğan conducted in prison, as if you really are calling her, without any irony, without any intermediary, and perhaps without any need for aesthetic mediation. The sound is turned on and an individual, who had been made invisible and inaudible, comes into existence. Thus, it is possible to regard each of these works by Zehra Doğan as an ontological insurrection, and the exhibition as an ontological (and of course political) restoration of honour.

This is in fact what Zehra Doğan wants: to add her voice to the stage of representation, to expose political violence on that stage in all its intensity, and if she can take a breather from this vortex of violence, to tell her personal tale, by transforming her own body into a device if necessary.

One last thing: in an interview, talking about the sense of freedom she got from her exhibition at the Tate Modern, Doğan said that she actually felt the bitterness of not being able to hold an exhibition in Turkey: “There is a certain sense of freedom here but it tastes somewhat bitter.” [5]

I suppose, with this exhibition, that bitterness is dispelled a little. One carnation, from hand to hand…

•

translated by ASLI MERTAN

FOOTNOTES

[1] It is possible to mention two other detainees who composed such a counter-manifesto: Parajanov who created ‘works’ with any material he could find in Soviet prisons and even used his fingernails to engrave metals if necessary, and the Kenyan author, Ngugi wa Thiong’o who wrote his novels on toilet paper while in prison and was nominated for the Nobel award. The writings of Selahattin Demirtaş and İdris Baluken who addressed the outside from the inside can also be included among these counter-manifestos, as texts or ‘textual political acts’.

[2] Wenda Mahmut Koyuncu, Ahmet Ergenç, “Bu Bir Sergi Değildir" (This Is Not an Exhibition) unlimiteddrag

[3] Butler, Judith; Precarious Life: The Power of Mourning and Violence.

[4] Osman Erden, Levent Çalıkoğlu, Şener Özmen: “Şener Özmen Ne İster?” (What Does Şener Özmen Want?) Sanatak

[5] To read this interview clearly explaining what Zehra Doğan wants, please refer to “Nusaybin'den Tate Modern'e Zehra Doğan'ın Hikâyesi" (From Nusaybin to Tate Modern, The Story of Zehra Doğan) Euronews.

Zehra Doğan’s first solo exhibition in Turkey Nehatîye Dîtın / Görülmemiştir/ Unseen is open for visits by appointment at Kıraathane İstanbul Edebiyat Evi until 9 November 2020.