Make room for Biberyan please

We need to make room for Zaven Biberyan in this country's literature. In my view this place should be somewhere at the top, among the very greatest

28 Mart 2019 11:30

“To tell the truth, I have to confess I regret writing in Armenian.”

Zaven Biberyan, December 3, 1962. In a letter to his friend Hrant Paluyan

I

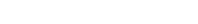

Zaven Biberyan’s novel, translated into Turkish in 1998 as Babam Aşkale'ye Gitmedi [My Father Didn’t Go to Aşkale], tells the story of a disaster. The story revolves around a father who is forced to sell everything after the implementation of a Wealth Tax- a levy that inflicted moral and material devastation on Turkey’s non-Muslim population during the years of the Second World War. By paying the tax he avoids being sent to the work camp at Aşkale and to a probable sorry end, but his family is shattered by the loss of status brought by this sudden impoverishment. Oppression, despair, fear, anger, hanging onto life but everything slipping away, dissolution, hitting rock bottom, the hope of bouncing back and then everything shattering to pieces over and over again. The disaster here is the Wealth Tax as experienced by the Tarhanyan family which we follow close detail in the text through their son Baret. The novel is long and impressive. It is unadulterated literature and considered to be the author’s masterpiece. Even though it was liked and appreciated by a small group of readers, it never reached a wider audience, was not widely written about not extensively discussed. In the new edition published; 49 years after its first serialization in Armenian, 35 years after its first publication as a book and 21 years after its first translation into Turkish; honor is restored with the reinstatement of the original Armenian title Sunset of the Ants and some miscellaneous untranslated or simply ignored passages that have also been restored to the text. This new book charts more useful routes to rethink the novel, Zaven Biberyan and his work; the nature and influence on the human of disasters (lowercase) and the Disaster (capitalized). We should take into consideration, that today, compared to 1998, we know so much more about these issues. Among these routes, perhaps the most interesting one, relates to the story of how for 21 years the Turkish translation of the novel could not be published with the right title and complete text, and even more strikingly, how this saga in itself confirms “the thing” the novel hopes to tell-- ultimately an aspect that is related to the Disaster itself. I will explain.

Sunset of the Ants begins on the day that Baret, an educated Armenian youth from Istanbul, returns from the 3.5 year-long, compulsory Nafia military service reserved for non-Muslims. After three and a half years of crushing rocks, building roads, living in tents and struggling with malaria, insects, nature, the mistreatment of sergeants, homesickness in all four corners of Anatolia; we expect Baret to embrace his homecoming with the ardor of a long-parted lover. On the contrary, the view that confronts us is icy cold. Baret knocks on the door and sees his mother Arus from the window. His mother, however, does not recognize her son. This first scene makes it feel like the two have drifted apart long ago. Finally recognizing Baret, Arus runs down the stairs, reaches the door, attempts to hug her son, but the response she receives is the first brick in the wall Baret will build around himself during the course of the novel:

“Don’t touch me, I’m filthy,” (…) “I’ve lice, don’t touch me.”

Even though Baret reunited with the home of his imagination, neither the home nor the inhabitants will be as they once were. He experiences a strong alienation from everything. It’s almost like he is paralyzed; he is there, he exists, he breathes, he comes and goes, yet it’s like he’s flowing along a stream –he doesn’t know what to do, what he wants, what he feels, he has virtually lost his will. What’s more, it’s as if he has transformed into a mere receiver, a recording machine. He does not have his own voice. He watches attentively, listens and comments but does not take action; he is incapable of so doing. He does not express opinions, talk to those around him about his state of mind or soul. Nor can he. He just swallows what he records as if it’s a black hole and not digesting or being able to digest he simply regurgitates various reactions. Meanwhile, life and Istanbul, regurgitate him.

Even though Baret reunited with the home of his imagination, neither the home nor the inhabitants will be as they once were. He experiences a strong alienation from everything. It’s almost like he is paralyzed; he is there, he exists, he breathes, he comes and goes, yet it’s like he’s flowing along a stream –he doesn’t know what to do, what he wants, what he feels, he has virtually lost his will. What’s more, it’s as if he has transformed into a mere receiver, a recording machine. He does not have his own voice. He watches attentively, listens and comments but does not take action; he is incapable of so doing. He does not express opinions, talk to those around him about his state of mind or soul. Nor can he. He just swallows what he records as if it’s a black hole and not digesting or being able to digest he simply regurgitates various reactions. Meanwhile, life and Istanbul, regurgitate him.

Biberyan always portrayed home and family as hell. In his other novels, such as Yalnızlar [The Lonely Ones] and Meteliksiz Aşıklar [Penniless Lovers] and as well in the latter Karıncaların Günbatımı [The Sunset of the Ants], family is a living hell that brings unhappiness to all members, but especially at the tenderest of ages it drains the young and blinds them with an indescribable anger. Here we see the soul-sucking hypocrisy, the malice, the calculating nature of the upper-middle class Istanbul Armenian family Biberyan knew so well in tatters. In this sense it reminds us of analysis we are familiar with in Western art: An exposé of the rottenness of the bourgeois family. For the bourgeois/ish segment of İstanbul Armenians, the family is the product of an unspoken traditional contract emerging essentially with the intention of gaining upward social mobility or securing basic comforts. For its participants Love plays no role in marriages or at least due to rootlessness, love is not transmitted to the next generations. So practically inevitably, these marriages become forced unions in which spouses despise one another but where the risk of abandoning a material comfort zone makes a break-up inconceivable. Biberyan himself belongs to this class and therefore he knows this milieu from within. Nonetheless he breaks off the contract of keeping silent. First he writes. Later, by becoming a communist, he is forced into class alienation, marginalization and insecurity for the rest of his life. The consequence among the children of the household of the absence of love, of the naked power struggle between grown-ups and of the games based on deceit, apart from the anger and resentment directed against their parents, are revolt, denial or apathy. Through this miniature universe Biberyan succeeds in expressing through internal monologues and dialogue and with a proficiency rarely seen elsewhere in our literature, confrontations and fights, people losing their temper or having fits of hysteria. As if it were the most natural thing in the world, he airs the dirty laundry of the urban, middle and upper-class family.

Even though his analysis is not false, it is incomplete. This is because the family that Biberyan portrays is different from the conventional, dissatisfied bourgeois family that readily feels ownership of the homeland it inhabits and relishes in that sense of ownership. They are the representatives of a minority group, marginalized, declared to be internal enemies, cursed. So no matter how hard they try to create and protect the fundamental need of their class, a safe space, in reality, they are the most vulnerable segment of society. Their values, accumulations, self-perceptions all rest on a weak foundation and their fates hang on rumour and hearsay; security of life and property is an illusion. Furthermore, no matter how much they try to forget, they are perpetually aware of this situation and this inner knowledge influences their every state, inflicting every moment of their daily lives. In front of us we have an Armenian family, which knows who among family members, were lost and how and in what conditions; despite this, they have somehow managed to survive, or rather the right to live in their own homeland was granted to them with the condition that they remain loyal citizens. Perhaps the worst part of it all is the perpetual waiting for new troubles to arrive, has turned their lives into a nightmare. This state of perpetual waiting in Biberyan’s works tells us that the Disaster goes on, it never ends. The Disaster is not the G word he never mentions, it is not in the least limited to that; it is indefinite, constant, eternal. Above all, when Biberyan is presenting all of this, rather than treating his characters as victims for their identities and victimhood, feeling sorry for them or trying to provoke with the intention of arousing pity, he tries with utmost dispassion to go down into the depths of their souls, and simultaneously into his own. Thus, the reader too can see and recognize his characters as stripped of all defenses.

No doubt the Tarhanyan family of The Ants, experienced deep traumas. At the very least, due to the Wealth Tax they were forced to sell everything they had, lose their social class and position within society, and were never again able to get back on their feet. No longer did they live in Mühürdar where they joyously watched the sky and deep blue sea from Gökyüzü Street. Instead, they lived in a house crumbling away on muddy-streeted Kuşdili where there was barely room to stand up straight. The source of trauma comes from the outside. Official or civil, all kinds of threats and danger are just beyond the threshold. Turkey, Istanbul. The country they live in, the place they were born and raised known to them as the homeland, has shown that it carries the potential of becoming a hell for them at any moment. It has become a cage in which they can never find peace. Yet it’s out of question to settle their account with the source of the trauma, this outside world. Settling accounts is such a horrifying, scary possibility that it can’t even be imagined. Haven’t they been so generously graced with the right to live? They must now shut up and behave. They must pound away, they must spare no effort to be able to endlessly feel that fake sense of safety. Towards the outside world they must be polite, loyal, understanding, skillful and obedient. They must be good neighbors. Like ants, they must rebuild life over and over again. They must do this, they must do that.

In this case, how can the pain, the pus, the poison ever drain? How will all this sorrow, this oppression be reflected externally? As a matter of course, that which is unable to seep out turns inward. First to the spouse; the wife’s to the husband, the husband’s to the wife; and certainly after, to the child once he/she grows up a little, reaches puberty and his/her tongue begins to grow sharp.

Thus while the actual war ends in the outside world and new horizons unfold like sheets for those who know how to take advantage of opportunities, for others the home has now unwittingly become a warzone. The incompetent father is rejected by his wife and daughter. He is impotent now. Everyone else is going about their own business, spinning their fortune but his time is over, his reputation as a doyen of the bazaar has long expired. Those grasping the spirit of the times; acquiring position, making money, living their lives and taking important roles in community works, are ascending. Baret is surprised to find his mother and sister taking a stand against his father. He has become a stranger now from whom even the sugar and coffee, obtained with great difficulty for the house, are hidden. They will not even believe that he is sick, albeit a while later he will die from that same disbelief; he had already avoided going to the workcamp in Aşkale out of fear that with his deteriorating health he wouldn’t be able to endure the conditions. For this decision, he was accused of being a “selfish” father, not thinking about the future of the family. Even though Baret does not completely surrender himself to the hostile winds blowing inside the house, he slowly becomes an accomplice on the battlefront set up against his father. And with the death of his father, he becomes even more reserved. He is overflowing with guilt, yet he blames his mother and sister for this death, he gets angry at them. Not knowing what to do with his anger, instead of staying and struggling through, trying to change the conditions, his solution is to leave. He runs away both from home and the job he had once embraced with enthusiasm but soon realized, in order to advance, he would have to sell his soul. He sinks into decadence in the backstreets, withering away in a freefall. The mother and daughter left behind, will not be able to do without an enemy and now will start nagging at each other. Through the energy they get from their mutual enmity they will be sucked in at full speed towards the vortex that will destroy them too.

Biberyan’s perennial male main characters, who cannot be called heroes, most of the time are hostile towards women. Their repressed sexual desires at times blow up, but not with the intention to express emotions and release, but with the need to define more clearly the boundaries between themselves and the opposite sex and to strengthen the established hierarchy in their minds. These learned men unfailingly bed less educated women from a lower class. Being with a woman belonging to the same social class and equal in terms of education could only be a dream and a source of unrest; they become mute around such women, they become childish. For them, the woman is a nemesis whom they either belittle or must belittle because previously some women belittled them.

Biberyan’s perennial male main characters, who cannot be called heroes, most of the time are hostile towards women. Their repressed sexual desires at times blow up, but not with the intention to express emotions and release, but with the need to define more clearly the boundaries between themselves and the opposite sex and to strengthen the established hierarchy in their minds. These learned men unfailingly bed less educated women from a lower class. Being with a woman belonging to the same social class and equal in terms of education could only be a dream and a source of unrest; they become mute around such women, they become childish. For them, the woman is a nemesis whom they either belittle or must belittle because previously some women belittled them.

While these passive individuals who are unable to direct their anger towards the outside source of the trauma ambitiously try to destroy each other, the son, who appears not to desire to be included in this game, as soon as he finds the first woman he can belittle outside of the household, sets out to vent out the pain of hate he feels for the opposite sex, his mother, his sister and in reality, everything and everyone. These young women from the lower class, who despite everything protect their inner innocence, are among the few women Biberyan depicts positively; like the ignorant, naïve and pure Lula of The Sunset of the Ants. However, it can be sensed that the author’s approach to these characters is a male-dominated perspective of idealization and objectification. If for instance these young women characters were given the chance to age a little, get married, have children, the ideal would easily fall apart; and so Lula could easily be swapped with Barets’s mom Arus, for whom he is full of anger and resentment.

Incapable of love, not caring in the least about the feelings of deep admiration and adoration Lula, fosters for him, Baret is of course shocked by the news that the young woman died while trying to abort the unwanted pregnancy for which he was responsible. Yet even in front of this horrifying situation, instead of facing up to his part in this bolt from the blue, he falls further into inexplicable darkness, continuing always to plunge deeper in the morass of his own evil. His departure from this situation occurs at the very moment he feels his life is slipping away altogether and takes the form of an escape to somewhere in the East of Anatolia. This is an entirely different environment which the author does not specify, apart from a few hints. It is a place whose identity we never discover but is somewhere Baret probably encountered during his Nafia military service period -the young man’s mysterious eastern adventure could have very well been the subject of another novel. Long after Baret returns from this voluntary exile we feel that he has pulled himself together a little; he has become simpler and tougher, but this probably will only suffice to keep him alive without losing his mind. It is probably a grasp strong enough for him to spend his life as a heavily wounded soul.

The ants of the Sunset of the Ants, i.e. the characters of the novel and what they represent, is a sunset followed by no twilight, no dawn, a sunset after which the morning sun will not rise, a vicious circle of a sunset. We see this through the lines at the end of the novel that announce the birth of a new disaster from the darkness. Life and property will disappear again; before the bleeding wounds heal, a new trauma will be added to the chain. Souls and families and many other things will once again fall apart. There is no escape. Disaster molds the souls. With or without, it poisons the relatively calm times and even the peaceful, serene moments.

II

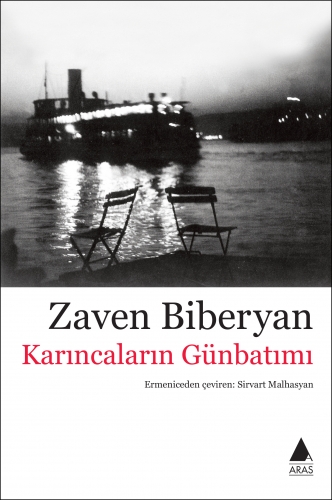

Zaven Biberyan was born in 1921 in the Çengelköy neighborhood of Istanbul and later moved to Kadıköy in the same city with his family where he was and ended up living for the rest of his life. He studied at the Dibar Grtaran Armenian and Saint Joseph French schools. The language that shaped him the most was French. Starting from his childhood until the age of 20, he wrote novels in French, which in his own words, “only worth tossing into the trash”. In 1940 when he was 19, he left the country, probably in order to escape from the increasing enmity against the Armenians and the malice coming to sight on the horizon. Yet he only made it as far as Bulgaria when the Nazis began to invade, after which he returned to his own country. For 42 months, from 1941 to 1944, like Baret from the Ants, he did his military service in the Nafia units with Armenian, Greek and Jewish men like him, aged between 20 and 45. In the letter, he wrote narrating the story of his life in 1962 to his writer friend Hrant Paluyan who lived in France, he describes this period as:

“Forty-two months in the mountains of Anatolia, from İzmir to the Georgian border, from the Black sea to Adana and Hatay. Always in tents. Fighting nature, hunger, tropical malaria. I lament these three and a half years. The best three and a half years of my youth, (spent) in wild mountains and forests.”

As a relatively more liberal wind blew through Turkey at the end of World War Two, a group of Armenians from the new generation came together and began to publish the Nor or (New Day) newspaper advocating socialist ideas. Biberyan had quit French in his Nafia days and had begun to write in Armenian which he improved by working diligently, by checking the spelling of every word in the dictionary. Despite all his perseverance, he would later say he regretted this decision. Through his sharp pen and industriousness, he became one of the most prominent figures in the Nor or group. However, along with left-wing newspapers in Turkish and unions that began publishing at the same period, Nor or was closed by the state, which was disturbed by too many winds of freedom flowing all at once. Biberyan and many Armenian writers and artists of a dissident stance like him were jailed, tortured and interrogated –with a twist of fate, at the Sanasaryan building which was a property expropriated from Armenian ownership. Many of these names –such as Vartan, Mari and Jak İhmalyan, Aram Pehlivanyan, Barkey Şamikyan, Hayk and Anjel Açıkgöz, S.K Zanku- were forced to emigrate abroad. These forced migrations proved a serious blow to Armenian literature produced in İstanbul which had been coming back to life for the first time since 1915. It virtually drained it of all vitality. Politically, this dissident voice that was becoming louder for the first time in the İstanbul Armenian community since the founding of the Republic would be silenced before it would ever get a chance to mature, and the free spirit suppressed there would not find a stream to flow into until 50 years later with Agos. Here, one must remember what kind of continuity the murder of the newspaper editor Hrant Dink who gave life to Agos, signals.

Biberyan’s later life tells the story of an intellectual destined to write, watching the trajectory of his country in parallel. His banishment to Lebanon which he wouldn’t remember with fondness, his return back home upon the softening of the political environment, the September 6-7 pogrom, and the May 27 coup which then followed. He saw the publication of The Lonely Ones (novel, 1959), “The Sea” (short story, 1961) and Penniless Lovers (novel, 1962). He became an unsuccessful candidate for parliament in the 1960s from TİP (Turkish Workers Party), but was elected as a municipal councilor for TİP, and was in and out of various jobs due to financial difficulties. Mrçünneru verçaluysı, The Sunset of the Ants, considered to be his masterpiece, was serialized in the Jamanak newspaper (1970). Then followed the March 12 coup and him not being able to publish his novel in book form. A long period of silence ensued. At that period he translated from French and English probably not only for the sake of intellectual curiosity, but to make ends meet. The small business ventures from toymaking to selling women’s lingerie at a stall he opened in Mahmutpaşa and his farewell to life in 1984 at the age 63 from (significantly!) an ulcer that followed the September 12 coup.

In the letter he wrote to Paluyan in 1962, Biberyan would say “If I honestly had to admit it, I regret writing in Armenian.” He had begun writing in French but had thought “Since I am Armenian I should write in Armenian”. The result were books each worthy of being masterpieces he published in a language nearly no one read anymore, no one would see, no one would discuss. Although he worked as hard as an ant his modest output contradicted his talent. Through his attachment to his country, his political struggle, his refusal to migrate, and his translations into Turkish, it is possible to discern a desire, at any cost, to find a channel of dialogue with Turkey and Turks. No matter how well he wrote, his milieu was not ready to listen to an Armenian writer, writing in Armenian, or the themes he wished to tackle. The reason for this lay primarily in his identity. Just as he says about Baret towards the end of the novel, for Biberyan, even if he began to write in French, later to return to Armenian and later yet to regret his decision, “Even though he realized was better not to be Armenian ”…It was impossible not to be Armenian.”

Despite being in this circle without exit, Biberyan’s stubborn perseverance to write and to struggle politically is as precious jewel in my eyes. Not imprisoning himself in the Armenian circles with whom he naturally quarreled, he insisted on positioning himself side by side with the Turkish intelligentsia and the Left-wing movement. His translations, his friendship with publishing circles in Cağaoğlu, his insistence on staying in İstanbul, all of these things made him more than a mere writer, it made him a stubborn resistor; an insurgent. Yet in the milieu he was involved with, was there anyone aware that he was writing novels in Armenian? Or was there anyone who was curious about what he wrote? Wanting to create, to speak, to not be silent, to show solidarity to him to end his silence? Unfortunately, we know that many of the answers to similar questions were not in the affirmative.

Those who knew him, describe Biberyan as a bad-tempered person who was difficult to communicate with. Just like the male main characters in his novels. What else could a man be if not quarrelsome after three and a half years crushing rocks throughout the four corners of Anatolia; a man who lived through the Wealth Tax, had been put behind bars, knew exile, the pogrom of September 6-7, experienced 3 coups, was defeated again and again, and who was disappointed again and again? Biberyan’s life is primarily a portrait of an intellectual, who, like the characters he treats in his novels, carries the trauma of the post Disaster brokenness in his being. Born and raised in an environment of alienation and enmity, a homeland where experiences are denied and is nearly always oppressing him for his world-view and identity, and the ordeal of tensions, ups and downs, dispersals experienced within the soul.

III

In 1970, Mrçünneru verçaluys, was serialized for 294 issues. It was also about to be collected into a book, when the March 12 coup occurred and Biberyan could not publish his novel as a book. Despite all this, giving the transcripts that he archived to a bookbinder, he was able to get the serial clippings to be bound into 10 copies and in this way he created a book prototype, with some autographed copies to be gifted to friends. For the novel not to be forgotten, for it not to gather dust between newspaper pages, for it to enter the bookshelves of some people who appreciate literature…. Aras obtained one of these books composed of bound serializations, autographed for Rupen Maşoyan and his educator wife Şoğer by his penpal –and who later, at an advanced age, becomes one of the founders of the Armenian newspaper, Agos. For many years it stands somberly in our bookshelf; a material manifestation of one of those moments in Biberyan’s Sisyphean struggle at the moment the rock rolls down to the foot of the mountain.

At this point he must have lost his patience, things must have really gone haywire because for the rest of his life Biberyan left nothing behind that has reached us. In the latter years, his health gradually deteriorated. While he was on his deathbed, a group of bibliophile women who wanted to give him a gift undertook the task of turning his Mrçünneru verçaluysı into a book and so Biberyan was able to hold his novel in his hands shortly before his death. We can only imagine how happy he must have been but unfortunately, it was to be a short-lived happiness. Soon after, on October 4, 1984 he lost his life and was buried in The section of the Şişli Armenian Cemetery reserved for intellectuals.

These people who appreciated him and his novel and gave him this sweet gift, facilitated the book in reaching us but due to obvious fears, certain passages were removed. We do not know whether or not it came to Zaven Biberyan’s knowledge, while he was in his sickbed; that passages especially related to 1915, the Disaster or contemporary political references, were not included in the book. We do not know if he approved of these changes. Though in any case, it is certain that censorship –perhaps auto-censorship- was applied to the text. Therefore the novel was published in 1984 in a form different from the previously serialized version. The 1998 translation into Turkish by Aras, took place without the knowledge of these cuts. One of the chapters that were removed was one sentence only and was about the characters of the novel being scared of what would happen to them because of the rising political tension:

These people who appreciated him and his novel and gave him this sweet gift, facilitated the book in reaching us but due to obvious fears, certain passages were removed. We do not know whether or not it came to Zaven Biberyan’s knowledge, while he was in his sickbed; that passages especially related to 1915, the Disaster or contemporary political references, were not included in the book. We do not know if he approved of these changes. Though in any case, it is certain that censorship –perhaps auto-censorship- was applied to the text. Therefore the novel was published in 1984 in a form different from the previously serialized version. The 1998 translation into Turkish by Aras, took place without the knowledge of these cuts. One of the chapters that were removed was one sentence only and was about the characters of the novel being scared of what would happen to them because of the rising political tension:

“In the end, we will bear the brunt and what we have left will also be gone.”

It is understood that the apprehension “In the end we will bear the brunt, and what we have left will also be gone” plays a role in the censorship of this and similar passages. That stereotypical question comes to mind: Was life imitating the novel, or was the novel imitating life? The removal of these passages took a serious toll on the text and in a sense left hanging, points which had been rounded off in the novel. These cuts prevented the emphasis on themes of perpetually waiting for something bad to happen, never being able to feel safe and not being able to give meaning to an existence where disaster always takes place. It obscured the reality that the novel ends on the night of September 6 1955 as it gives way to September 7, at the sunset of the ants, as smoke and noise rise from somewhere in the city, obscuring the frame of emotions it creates.

In the last resort, those who read the book in Turkish, interpreting the novel in the absence of these passages, were left unaware of the truly striking aspect of the novel. Another major intervention was the book not being published with its original name but as My Father Did not Go to Aşkale. At the time the Wealth Tax was being heavily discussed by the public because Yılmaz Karakoyunlu’s novel Salkım Hanım’ın Taneleri and Tomris Giritlioğlu’s film adaptation of it had just been issued. Aras thought it appropriate to give the book this title on the grounds that the topicality of this discussion would benefit the novel of an unknown Armenian writer being published for the first time in Turkish. But this decision and the way the book was presented, caused the world of meaning of the novel to be limited to the Wealth Tax and created a situation which obstructed the realization and deciphering of the layered structure of the text. So once again another interference in Biberyan’s novel, even with good intentions, resulted in a bad outcome.

After the Turkish translation was published, a friend of ours who knew well the background of the story, pointed out the differences, the censorship between the serialized text and the printed Armenian book. Although we were surprised and upset, I can’t say that it came as a big shock. For all Armenians, including ourselves, throughout the history of the Republic boundaries have always been present as to what could be said and how it could be said. But the times had gradually changed and Turkey had moved towards a relative climate of freedom (damn it relative, always relative!) and both for this reason and in order to respect the memory of Biberyan, the Armenian edition we produced in 2007, the novel was published for the first time in its totality and in what I suppose I might describe as, a definitive version.

But the story doesn’t end there. Inasmuch as the Turkish edition was based on the original and should have been without omissions but, as a result of some sort of malfunction- or perhaps we should call it a lapsus- only four out of six of the passages that had been removed from the book were added to the Turkish text. And so, the single sentence quoted above was omitted along with the passage below of vital importance for the main point of the novel. Therefore, the edition published in Turkish in 2013, still entitled My Father Didn’t go To Aşkale squandered the opportunity to be a complete, text without even realizing what had been lost.

“Yesterday the Wealth Tax, today Cyprus, tomorrow something else. But always a disaster for which we have to take the blame. “Something will come out of it’. This was what disturbed him, (…) Undoubtedly, for all those years he had forgotten what it meant to be an Armenian. He was trying to remember and as soon as he got over the first shock, he was beginning to understand what this meant now. Without meaning to, he was again assuming his Armenian identity. (…) He was realizing that it was easier ‘not to be Armenian.” But it was impossible not to be Armenian.

(…) Perhaps the problem was exactly this, they were so comfortable and they were not used to so much comfort, the nearness of a disaster was always gnawing away the hours. They were winning, eating, drinking, having fun but there was a rush in this way of living; as if they were on a sinking boat. They were expecting something to happen at any moment. A confusion. Compared to 10 years previously, they were more afraid. Because they were satisfied with their situations and they didn’t want anything to change.

“We got used to it, Ms. Arus…. The Disaster…”

“They could not feel at ease without the disaster. An aspect of their lives was missing. They were waiting for something. Because they could not imagine a monotone life without a disaster to last forever. Ten years was too much.”

IV

Should such “forgetfulness” be accepted as an example of the great difficulty endured, while trying to break the habits of minds which have accepted being hushed and silenced as the norm, even while attempting to raise their voice in challenge? Having once been silenced and having accepted that their voice be stilled, and knowing and internalizing that reversing this behavior will pose a danger, how could the voice that decides to speak out not emerge broken and faltering? It seems to me that there is an influence of our various repressions; in our falling into an editorial mistake while lifting the curtain off the silenced passages in The Ants; in the clumsiness in our repeated inability to bring the text back to its initial state in its entirety. That cursed fear that the Disaster and the disasters are there, always by our side, shaping us and at times paralyzing us like this, even while we are at our most courageous.

In 2017, we translated Zaven Biberyan’s first novel Penniless Lovers into Turkish and we asked literature professor Marc Nichanian who came to Istanbul upon the invitation of Sabancı University to write an introduction for this book. Nichanian is known for his works on the Disaster and the impossibility of explaining the it, and who has made substantial contributions for the development of this literature and who has opened the horizons of many of us on this issue, Nichanian was also the first to write a critique on Mrçünneru verçaluysı published in Paris in 1985 and to draw attention to the importance of the novel. In the introduction he wrote for Penniless Lovers too, while describing the influence of the Disaster on Biberyan’s novel, he quoted a passage from The Ants. When we began to turn the pages of the Turkish 2013 edition of the book we thought we had published in full to find this quote he had made from the Armenian text, we saw that the passage Nichanian had quoted was not in the text. It simply wasn’t there. More precisely, it was in the Armenian but not in the Turkish version. The part, a researcher who was born and raised not in Turkey but in France and who read in Armenian, had ascribed prime importance to, was at present unavailable for neither the Turkish readers nor for us Armenians of Turkey.

To cut a long story short, translating this quote from the Armenian text for the first time, we published it in the preface of Penniless Lovers and during the editorial department meetings we had in those days, we decided to put together the next Turkish edition, by thoroughly comparing the serialized text with the Armenian text. Eventually, we realized the book that is now available in bookstores and we hope that this time it is finally truly complete. While producing this edition, and thinking it would be wrong to frame the text in terms of the Wealth Tax and Aşkale (especially since the emphasizes made in the newly included passages very conspicuously reveal the significance of The Sunset of the Ants) we gave the novel its original title back. We committed a publishing sin by summarizing the process I explained here in detail in the preface of the book, and in the end, we additionally listed the parts we added to the text in the 2013 and 2019 editions.

I didn’t explain all of this for it only to be self-criticism of my editorial incompetence –although the necessity of this is obvious. My hope is, that the life story of a writer who intended to understand and tell what the Disaster and disasters did to people, life, woman, man, family, society; and whose work was shaped by the same Disaster and post-Disaster environment and what he dared to tell by tearing to pieces his silence, because read and discerned by us shaped unavoidably by the post Disaster environment, the narrative, the story and where life again returns into itself, to repeat itself in different forms and this vicious cycle, the consequences of the Disaster, its wound, its pain, its trauma does not reveal any other paths to take other than to confirm once again the impossibility of explaining all of this.*

What was experienced, was again a sunset vicious cycle. In spite of Baret who became mute, Baret who could only exist by observing and listening and in the end by running away, there was Biberyan who didn’t run away, who didn’t leave, who fostered the hope that despite everything he would be understood. The defeat he repeatedly endured, the conversation he conducted virtually without an interlocutor, his incessant nightmares becoming so repetitive that, even after his death, in the translation of his book into Turkish, in the new editions being published; the words, sentences, paragraphs, pages are muted, silenced, evaporated into thin air, and above all, sometimes without even being noticed.

Is there a way out of here? I don’t know. I guess the only information we have in our hands since Zaven Biberyan is a writer; he couldn’t find a way out other than through writing; is that he wanted to be listened to, heard, read and understood. Not just as a writer, but also as a human being. Unfortunately, now that he’s gone, the only way to understand him is through his work. To speak to him through his work, to discuss it. We are not referring here to a kind of burden that could only be an ethical concern in understanding a person, in developing empathy for them. We are talking about a literary corpus, three very well written novels, the stories we will publish in Turkish towards the end of this year and an 800-odd page French autobiography that will be translated into Turkish next year. This is the legacy of a writer, who doubtless if he had lived under different circumstances, could have been undeniably much more productive.

As a final word, I would like to tie in the story. We need to make room for Zaven Biberyan in this country's literature. In my personal opinion, this place should be somewhere at the top, amongst the greatest. But greatness, the magnitude is not so important. What is important is, for there to be a place. Maybe a place that can compensate the home Baret returned to, but couldn’t find. In 2000, in one of the prestigious bookstores in Ankara, which I had gone to in order to attend a book fair, I saw Biberyan’s Lonely Ones on the “World Literature” shelf. I was sad to see that Biberyan is seen as a foreigner even though he had stubbornly resisted and persisted in remaining in Turkey and who would not allow The Lonely Ones to be translated into Turkish by anyone other than himself, who had thus rewritten the book in Turkish. I agree too that Biberyan is a world-class writer, but he first needs to take his place in the bookstores of his own country. I hope that The Sunset of the Ants will enable this to happen.

Translated from the Turkish by Melek Hamer

* Friends of mine who read the piece told me that this paragraph is the most critical part of the text, but the last sentence is too long and too difficult to understand and revising it again would be good. They’re very right. But because I am afraid that if I try to elaborate; to make it easier to understand, to express myself in properer sentences, I won’t be able to pull it off and I will express my point in an even worse way; I left it as I first wrote it, as it is. If you could bear with me until now, I am hoping that you can more or less understand what I mean.